📁RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

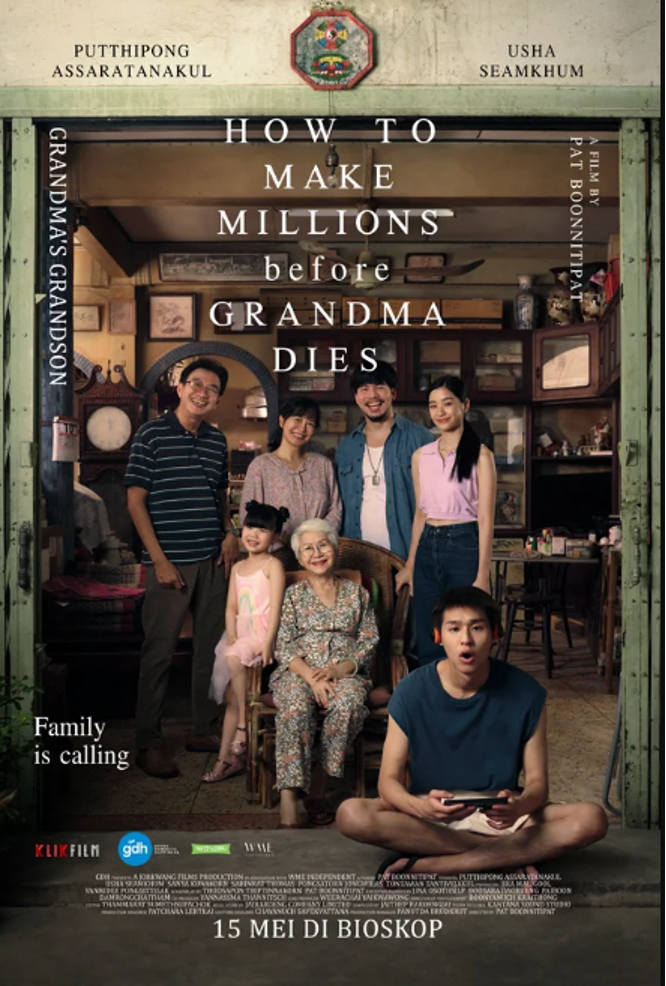

Pat Boonnitipat (director), How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies, 2024. 127 min.

This review may contain spoilers.

Dare I say it, Pat Boonnitipat’s How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies is the best family drama film of 2024, if not the decade. His direction is simple and straightforward. It is not bogged down by overly dramatic dialogue, shouting, slapping, or physical tension. The film’s strength lies in the simplest details—buttons, kettles, and pomegranates wrapped in plastic bags—all packed with subliminal messages and a certain magic that tugs at the heartstrings of viewers.

The matriarch in the film, Mengju (Usha Seamkhum)—or Amah to her flesh and blood—suffers from late-stage colon cancer and only has one year left to live. Her grandson, M (Putthipong Assaratanakul), sees it as an opportunity to secure his share of the inheritance, so he leaves his job as a gaming streamer to look after his dying grandmother and earn the top spot in her heart. However, what started as an economic motivation eventually shifts from self-interest to genuine care and affection for his Amah, showcasing a beautiful character development arc that is both realistic and deeply touching.

One of the most interesting aspects of the film is its bold exploration of feminism and gender dynamics within the family. Throughout the film, it becomes apparent to the viewers that Menju is biased towards her sons, even with Soei (Pongsatorn Jongwilas), her youngest, who eventually steals her stash. “Sons get assets, daughters get cancer,” Chew, M’s mother (Sarinrat Thomas) blurts out in one of their conversations with Amah. Amah’s preference for her sons is a reflection of the generational bias she herself experienced as a young woman; we later get to learn that when her parents died, almost all their wealth, including the family home, went to her brother. These glimpses of gender inequality reflect ingrained societal norms that privilege men and marginalise women, a deeply rooted issue that resonates strongly not only in the context of Thailand, but in many countries in Southeast Asia. The film handles this delicate issue with grace, offering a critical view on how these biases are perpetuated and the sad impact they have on transgenerational family dynamics.

The film also deftly uses space to highlight the differences in lifestyle and values within the family. The stark contrast between the spacious state-of-the-art abode of Mengju’s eldest son (Sanya Kunakorn), and her own small and humble home, where the kitchen and living room are basically in one place, is a powerful visual metaphor for the difference in their lives. This cinematographic strategy is not random nor devoid of meaning. This dichotomy in spatiality not only emphasises their economic differences but also the emotional and psychological distance between family members. The cinematography enhances the film’s intimate atmosphere, particularly through the use of a warm color palette and shallow spaces when in Mengju’s home, effectively creating a sense of home amid the hustle and bustle of Thailand.

The representation of Thai-Chinese culture plays an important role in the film, particularly through language and traditions. The older characters often switch between Thai and Thai-Chinese in their conversations, highlighting their dual heritage, but only Mui (Tontawan Tantivejakul) among the young characters knows how to speak Thai-Chinese, reflecting the tragedy of translanguaging in their clan. This bilingual representation not only adds authenticity but also deepens the portrayal of their cultural identity. The family also continues to celebrate traditional Chinese holidays such as Lunar New Year and Tomb Sweeping Day, which serve as poignant reminders of their shared heritage and the enduring bonds of family.

The acting in the film is stellar, and the actors portray their characters brilliantly. Usha Seamkhum in particular brings a delicate balance of strength and vulnerability to life, making Mengju a very sympathetic character. When the film credits started playing, I felt tears streaming down my cheeks as my mind immediately went back to the days when my Inang (Ilocano word for grandmother) would play and take care of me when I was still a kid in rural Tarlac. I wish I had played more card games with her, bought her more shoes, and spent more time making porridge with her; never mind that it was too runny—we both liked it that way, and that’s what mattered. I hope my Inang knows that she holds first place in my heart.

I wish I had millions to buy my Inang a “house,” a sanctuary worthy of her grace.

How to cite: Baysa, Rhanydell Bien.“Amah, You’re My First Place: Pat Boonnitipat’s How to Make Millions Before Grandma Dies.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 19 Jun. 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/06/19/make-millions.

Rhanydell Bien Baysa wrote his first poem about balls at age seven when he got hit by one in a local playground. Since then, his sports skills has not improved, but he likes to think his articulacy has. He was a fellow at the 2023 Cordillera Creative Writing Workshop and an active member of UPB Literati and Ubbog Cordillera Writers. His works have appeared in various local and international publications; one of his poems won the 2nd Place for the Land Rights Artist Prize held by the International Land Coalition. Now a Baguio-based activist who writes in English, Filipino, and Ilocano, he is pursuing his bachelor’s degree in language and literature at the University of the Philippines Baguio.