📁RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Violets.

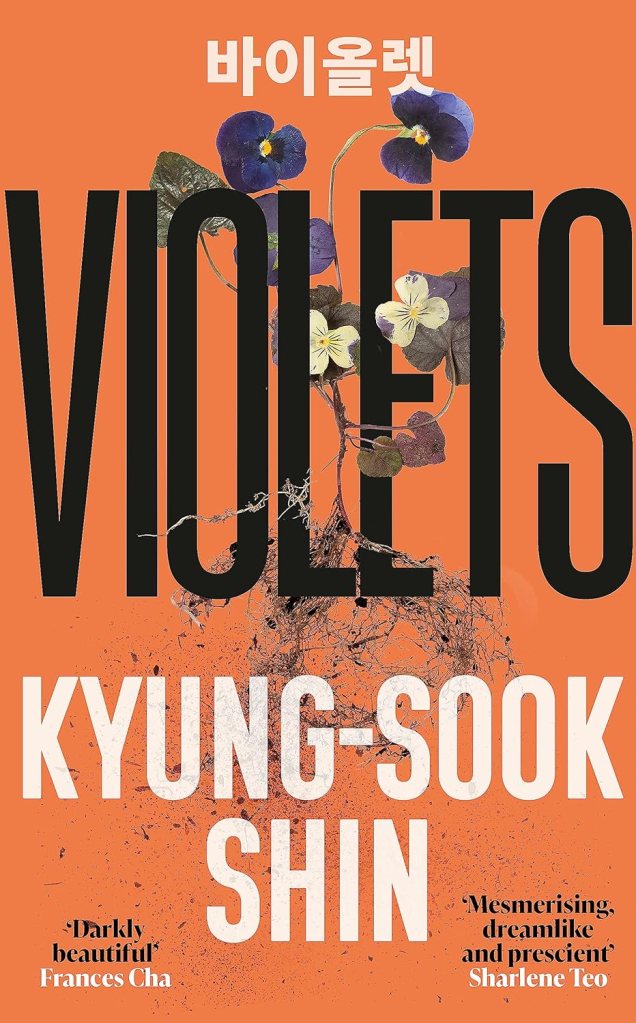

Kyung-sook Shin (author), Anton Hur (translator), Violets, The Feminist Press, 2022. 218 pgs.

I fell in love with Kyung-sook Shin’s writing after reading the novel Please Look After Mom. So I was delighted when I found Violets, a story I hoped I would enjoy as much. And it did not disappoint.

I will briefly outline the book’s narrative without going into detail. On the one hand, because I don’t want to spoil the pleasure of reading, of discovering the story. On the other hand, because what makes Violets, translated by Anton Hur, a special book (I’ll refrain from using stronger words, although it’s worth it) is not so much the story itself, but the style in which it is told. Kyung-sook Shin’s writing is what creates the right atmosphere, tone, characters and especially that hard-to-write South Korean melancholy, that characteristic South Korean han that doesn’t shy away from literature either. Han, a concept in South Korean culture, a collective feeling of sadness, a kind of isolation and retreat from injustice that comes from the traumatic history of this nation.

Returning to Violets, it begins with a foray into the atmosphere of a humid summer in a traditionalist village, where a woman gives birth to a baby girl. For those unfamiliar with certain things in South Korean culture, giving birth to a girl and not a boy could once have been a stigma. We are talking about a deeply patriarchal society, and that affects lives in every way. It is also the reason the girl’s father soon leaves home, abandoning his family. Her mother thus becomes the first divorced woman in the village, with all the humiliation that entails. Struggling to survive, the little girl grows up, but with a deep sense of loneliness, rendered very intensely, without the author dwelling on it at length. That’s because everything in her writing is well calibrated. In her solitude, the little girl, San, befriends another, Namae. A peculiar friendship, against a peculiar background, but one that ends abruptly and somewhat aggressively, as San crosses a line of physical closeness of which she had been unaware. A gesture of no return, which throws her onto another level of loneliness, into a hostile environment, where her only companions are her mother and a cantankerous grandmother.

Fast-forward to San at the age of 22, in Seoul, looking for a job. A tumultuous city full of opportunities, but one that is in no hurry to assimilate you, you have to work hard to get under its skin. After failing to get a job at a publishing house, she sees an ad for a job at a flower shop, work she knows nothing about but dares to try. Here she befriends her colleague Su-ae, of a complete opposite nature, with whom she ends up living. One day, a photographer comes to the flower shop to take pictures of some flowers for a magazine and notices San, otherwise invisible to most people. He takes her picture, too, designed to liven up the picture of violets for the magazine, which he finds dull and boring. This small incident completely changes San’s monotonous life, sets in motion some repressed mechanisms, and so the possibility of change, perhaps even happiness, is glimpsed. But things are not that simple. Traumas don’t just disappear; they work and pull you back, even if you don’t always realise it. A nagging doubt and insecurity always holds San back, as if she is not capable of happiness, of life, after all. There is always that unseen but somehow palpable impression that happiness is as fleeting as possible for her, that it always slips through her fingers. San slips into a veritable obsession with the photographer who awakens in her the promise of sexual desire and intimacy, which she had blocked out since the incident with her childhood friend.

What happens next, I’ll let readers discover for themselves. What is certain is that the story and its meanings build up, intensify and keep you captivated in the book until the end. And once again I say, its magnetism also comes from the atmosphere, the backdrop against which the characters move, all created in a subtle style, completely different from the clunky descriptive styles of past literature. The evil is always there, but you don’t see it. You can at best intuit it, though you will never be able to outline its clear outline. That’s why the ending almost slams you to the ground. It’s to the credit of a very good narrator. The title is not at all accidental, it is also an offshoot of the story. At one point, fascinated by violets, those seemingly commonplace flowers that the world in general ignores, she looks up the meaning of the word in the dictionary. But in looking up the word, she sees that the dictionary is mixed up with others, whose connotations are important, we will eventually see: “violets, viol, rape, rapist”, she reads from the dictionary. All the details are important, the reader must keep that in mind.

Essentially, this is a novel of the condition of women in a male-dominated world. Her delicacy in an environment where their predatory attitude is encountered at every turn. They can always take what they want, as much as they want, whether she, the woman, allows it or not. Their aggressiveness is everywhere, San sees it in some families, with colleagues, on the street and so on. A misogynistic tapestry discreetly weaves itself and surrounds San from beginning to end. It is one of the recurring themes of contemporary South Korean literature. The story of the many women who go unnoticed like violets mistaken for weeds and who struggle to make their way through the deeply traditionalist masculine maze that dominates their society.

As I said, the ending is unexpected and heartbreaking.

How to cite: Tataran, Dorina. “Keeping You Captivated: Kyung-sook Shin’s Violets.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 20 Jun. 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/06/20/kyung-sook-shin-violets.

Dorina Tataran is from Bucharest, Romania. After being a journalist for several years, she has returned to her first love: books. She has been translating books from English into Romanian for over ten years now and from Asian literature she translated Weina Dal Randel’s The Empress of Bright Moon. She is also one of the editors of the online cultural magazine Semnebune.ro. She has published a few short stories in a local magazine and some excerpts from a novel-in-progress in a few others. She is passionate about Asian culture in general, and she is currently learning Korean and discovering more about South Korean culture, especially its literature and films. Dorina loves jazz, coffee and she thinks there is nothing more exciting than being a spectator of this ever-changing world, especially through its stories.