➑➒➏➍

[Return to Table of Contents.]

Matches Polished into Lights:

Tiananmen Thirty Years On

(Mon 3 June 2019; 730 pm)

Cha and PEN Hong Kong

Media support: Hong Kong Free Press

Venue: Bleak House Books

Moderator: Tammy Ho

SET ONE

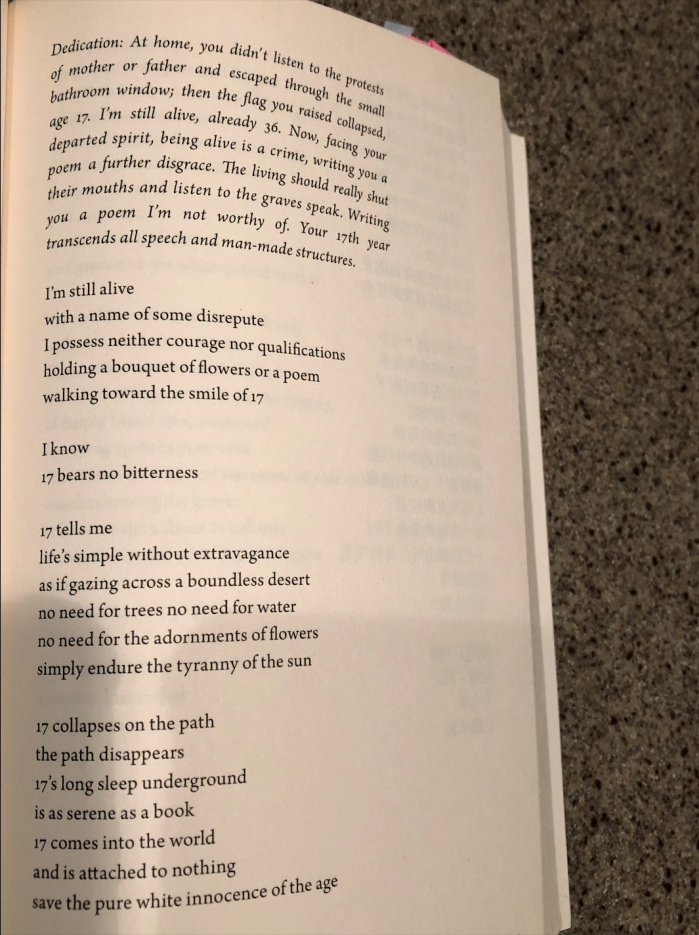

- Liu Xiaobo’s “For 17”

SET TWO

- Louisa Lim’s “Preface” to 《重返天安門》(an excerpt)

When I wrote my book, I did not realise that I would end up unlocking—or unleashing—those forbidden memories. But in the dozens of talks I have given at universities in the US, the UK, Hong Kong, Germany and Australia over the past five years, time after time I have seen that process happening before my eyes. In talks, I draw upon official sources like mainland newspapers, propaganda leaflets and internal reports, as well as using photographs and diaries of the time. To some members of the audience, seeing these artefacts is their first exposure to knowledge that can no longer be unknown.

At one of my first talks in 2014, a Chinese woman stood up to ask a question. She wanted to know whether the student movement had received aid from overseas. Her thin body was visibly shaking and her quiet voice quavered, as she followed up with a question that was more like a plea for mercy, “Was anything that we were told by the authorities true?” she asked, “Any of it at all?” The choice of active not-knowing that she had made so many years ago had just been forcibly removed.

At a midwestern university, I had noticed the stillness of a young Chinese student who had sat there transfixed, listening. After I finished talking, she spoke out in front of a room full of American classmates. “I spent eighteen years of my life in China and I realise now that I know nothing about my own country’s history,” she said. “I went to the best schools, the most well-regulated schools. And I know nothing about anything.” Her time of non-knowledge was over.

For witnesses, forgetting was a therapeutic reflex. I met people who had protested in Chengdu as students, who had witnessed the bloody crackdown and promptly wiped it from their memories. “Until I heard your talk, I myself forgot that I had been there,” one woman told me in the United Kingdom. For some, amnesia was a therapeutic act of self-protection to guard against massive trauma, for others the pain was in the crushing disappointment that followed those seven euphoric weeks of hope and optimism.

Journalism professor Michael Schudson writes that public events allow a society to think out loud about itself. But when memory of public events is suppressed, there can be no accountability, no act of reckoning. Over time, it became clear to me that some young Chinese actively embrace not-knowing as the better, safer option. Their logic is that the government’s decision was clearly correct, and any deviance from that could prove foolhardy, even dangerous. At an Australian university in June 2019, a young woman stood up after the talk to ask, “Why do we have to look back to this time in history? Why do you think it will be helpful to current and nowadays China, especially our young generation? Do you think it could be harmful to what the Chinese government calls the ‘harmonious society?’” Afterwards, another Chines student came up to me, and asked whether knowledge of June Fourth could be harmful for “our perfect society”.

The hardest question of all for me to answer was one that I was often asked surreptitiously, by young Chinese who would hang around after the end of the talk, waiting for others to leave so they could have an unguarded conversation. They would sidle up to the table, and ask – sometimes so quietly that I could hardly hear—different variations of the same question. In it was an unvoiced accusation, for I had pierced their ignorance, and that act could not be undone. What they wanted to know was what to do with this new knowledge weighing them down. How were they to use it, now they had it? Find out more, I would tell them. Read all that you can about what happened. Use the freedoms available to you to make up your own mind about what version of your country’s history you accept. Tell other people, if you want. But above all, just remember. In the words of Liu Xiaobo, from his fifteenth elegy for June Fourth,

绝望中

记住亡灵

是唯一的希望

Hong Kong April 2019

Louisa Lim is an award-winning journalist and the author of The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited (Oxford University Press, 2014), which was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize. She now works as a Senior Lecturer in Audiovisual Journalism at the University of Melbourne. She reported from China for a decade for NPR and the BBC, and she now co-hosts The Little Red Podcast, which won the News and Current Affairs award at the 2018 Australian Podcast Awards. She is a contributor to Cha‘s “Tiananmen Thirty Years On” feature in the June 2019 issue of the journal.

[Louisa Lim: A featured reader at “Matches Polished into Lights: Tiananmen Thirty Years On”—a reading jointly organised by Cha and PEN Hong Kong, on Monday 3 June 2019.]