📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

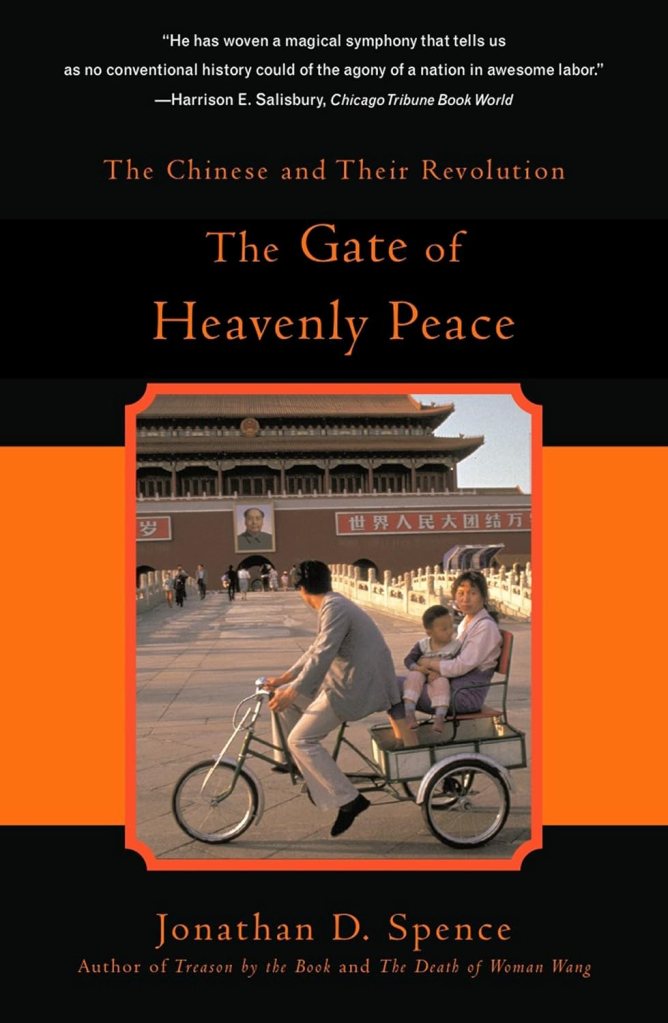

Jonathan D. Spence, The Gate of Heavenly Peace: The Chinese and Their Revolution, Penguin, 1982. 560 pgs.

Contrary to what the title might suggest, Jonathan D. Spence’s The Gate of Heavenly Peace doesn’t depict a tranquil narrative. Instead, it unfolds against the monumental backdrop of the Gate of Heavenly Peace—Tiananmen—a gate located in central Beijing that leads to the heart of the imperial city. This gate serves as the setting for some of the most consequential events that shaped China’s 20th-century history.

Spence’s work delves into the tumultuous events characterising the “Chinese Revolution” from the late 19th century through to the 1980s. It spans from the turbulent final years of the Qing dynasty to the era of Deng Xiaoping’s reform and opening-up. Through meticulous historical analysis, Spence provides a comprehensive exploration of this critical period in China’s history.

In addition to important Chinese political figures from between 1895 and 1980, such as Sun Yat-sen, Yuan Shi-kai, Chiang Kai-shek, and Mao Zedong, Spence also focuses on Kang Youwei, Lu Xun, and Ding Ling, who wielded significant influence over the philosophy, political thought, and modernisation of their time, leaving an indelible mark on Chinese literature and intellectual life.

The book also covers the experiences of other influential authors who played pivotal roles in the political landscape of the era. Personalities like the illustrious Qiu Jin, a pioneer of feminism in China, and distinguished figures such as Liang Qichao, Shen Congwen, Qu Qiubai, Mao Dun, Guo Moruo, Xu Zhimo, Wen Yiduo, and Lao She emerge, each contributing their unique voice to create a vivid and comprehensive portrait of the historical and intellectual milieu they inhabited.

In a departure from the conventional narrative centred on Sun Yat-sen in the fall of Imperial China, Spence redirects attention to Kang Youwei, a young scholar who followed a more traditional Confucian path and emerged as a rival to Sun among the young rebels. Kang’s tale unfolds with his success in persuading the emperor that there was an imperative need for modernising political, social, military, and educational institutions. This effort culminated in the ill-fated “Hundred Days Movement”, where both Kang and the emperor faced a coup d’état orchestrated by the Empress Dowager. Remarkably, this coup occurred approximately a hundred days after the beginning of the modernisation movement.

Subsequent to their overthrow, Kang embarked on a purposeless global journey. Even during the eruption of the 1911 revolution, known as the Xinhai Revolution, Kang maintained a moderate stance, exerting influence amid the tumultuous events unfolding in China. His death in 1927 coincided with intense conflicts between communists and nationalists. Nevertheless, Kang’s death attire—ceremonial robes—symbolised his unwavering adherence to traditional Confucian principles.

Meanwhile, Spence introduces us to other prominent figures, such as the aforementioned Qiu Jin, renowned for her pioneering role in the feminist cause. Her political advocacy for women’s rights is intricately interwoven with her active participation in the revolutionary movements aimed at overthrowing the Manchurian Empire. Qiu Jin emerges as a symbol of courage and determination in the history of the struggle for women’s emancipation in China.

Another noteworthy figure is Qu Qiubai. Following his mother’s tragic suicide, the young poet ventured to Beijing in pursuit of fortune, his arrival coinciding with the May Fourth Movement of 1919. When there, he had the opportunity to go to the Soviet Union, where his poetry took on a political dimension, merging seamlessly with the study of Marxism.

Adding to the tapestry of this period are the poet aesthetes Xu Zhimo and Wen Yiduo. In contrast to Qu Qiubai, they were from more affluent backgrounds, affording them the opportunity to study abroad—Xu Zhimo in the United States and Cambridge, and Wen Yiduo in the United States.

Yet, it is the figure of the great author Lu Xun who undeniably dominates the central part of the book. While Lu Xun may not have held an official political title or leadership role, his political impact resonates through his intellectual contributions and literary works, significantly influencing public opinion and critical thinking in 20th-century China. Politically, his refusal to unquestioningly align with the Communists, coupled with his opposition to the Nationalists, places him as emblematic of an enigmatic circle of intellectuals whose narratives are seldom brought to light.

Lu Xun advocated for progressive and democratic ideals, openly critiquing the conservative traditions and regressive elements within Chinese society during his lifetime. His most renowned works addressed social injustices, political corruption, and the imperative need for cultural reform in China.

Following Lu Xun’s deaths in 1936, Spence’s narrative transitions to Ding Ling, a pivotal figure who, even prior to embracing communism, had already left an indelible mark as a feminist writer. Ding Ling stands out as one of the pioneering women to achieve prominence in the realm of modern Chinese literature. Beyond her literary prowess, she was an active political participant, having joined the Communist Party and engaging in the struggle against nationalist rule.

After the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, Ding Ling assumed significant roles in culture and literature. She garnered prestigious accolades, including the Stalin Prize for her novel The Sun Shines over the Sanggan River. However, like many intellectuals, she experienced a fall from grace during the Cultural Revolution.

In his book, Spence translates the reflections of these characters on the failures of their times and their hopes for the future, presenting a spectrum of emotions ranging from joy to sorrow, humour to poignant melancholy. Many of these individuals encountered tragic fates, facing death or heartbreaking suffering amid the massive upheavals that reshaped China during that period. The narrative of these personal experiences adds a layer of empathy and comprehension to the intricate historical dynamics of the era, rendering the narrative, in my opinion, even more captivating and moving.

In this context, it is essential to underscore Spence’s skill. Despite drawing on a diverse array of materials from the principal works of these authors, quoted in his book, he succeeded in weaving a rich and coherent narrative. This work, serving as both a historical account and a literary resource, is enhanced by excerpts from celebrated works such as Kang Youwei’s The Book of the Great Community, Medicine, Diary of a Madman and The True Story of Ah Q by Lu Xun, along with Mengke and Diary of Miss Sophie by Ding Ling.

Spence not only deviates from the conventional portrayal of historical events but also in his selection of events to cover. Contrary to the typical focus on well-known historical occurrences such as the Northern Expedition, the Long March, the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Civil War, and the Great Leap Forward—events that precipitated significant social and political upheavals in twentieth-century China—Spence accords them secondary importance in this book. Instead, the narrative centres on the events surrounding the Gate of Heavenly Peace, the monument from which the book derives its title. It provides detailed accounts of happenings that prompted millions of young people to take to the streets, expressing their concerns and advocating for social and political change or supporting party leaders’ initiatives, as seen in the 1966 rally.

Key events covered include the May Fourth Movement (1919), the upheavals in China between 1925 and 1926, remembered as the May Thirtieth Movement and March 18 Massacre (Wen Yiduo wrote a poem titled “The Gate of Heavenly Peace” about this event), the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966), and the death of Premier Zhou Enlai (5 April 1976).

The Gate of Heavenly Peace provides an illuminating journey into China’s intellectual development since 1895. Instead of navigating the familiar currents of military and political struggles, the reader is guided through the thoughts, emotions, and personal experiences of key writers from this transforming period. By focusing on writers and intellectuals rather than conventional figures of power, such as politicians or generals, the narrative acquires a human dimension, emphasising the challenges and uncertainties faced by individuals during tumultuous times. The book, while briefly mentioning crucial historical events, primarily focuses on the impact of history on individual lives, making it a compelling and distinctive read. For these reasons, I recommend this book to anyone seeking a clearer understanding of the true protagonists of the “Chinese Revolution”, which led to the fall of the Qing Dynasty and the subsequent modernisation of a China that, as noted by Spence in the book’s final pages (bearing in mind it was written in the early 1980s), still had a long road ahead of it at that time.

How to cite: Marini, Alessia. “An Illuminating Journey: Jonathan D. Spence’s The Gate of Heavenly Peace.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 23 May 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/05/23/heavenly-peace.

Alessia Marini is an MA student in Language and Civilization of Asia and Mediterranean Africa, curriculum China, at Ca’ Foscari University in Venice. Graduating with honours from Ca’ Foscari University in 2022, she furthered her studies by attending Chinese studies and Chinese language courses at National Chung Hsing University in Taichung from September 2023 to January 2024 as a visiting student. Her academic interests revolve around contemporary Chinese history, with a particular emphasis on the development of education. She is currently writing a master’s thesis on the role of primary education in nationalist indoctrination in Taiwan, with a specific focus on school textbooks from the martial law period.