📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Click HERE to read all entries in Cha on Nightmare Japan.

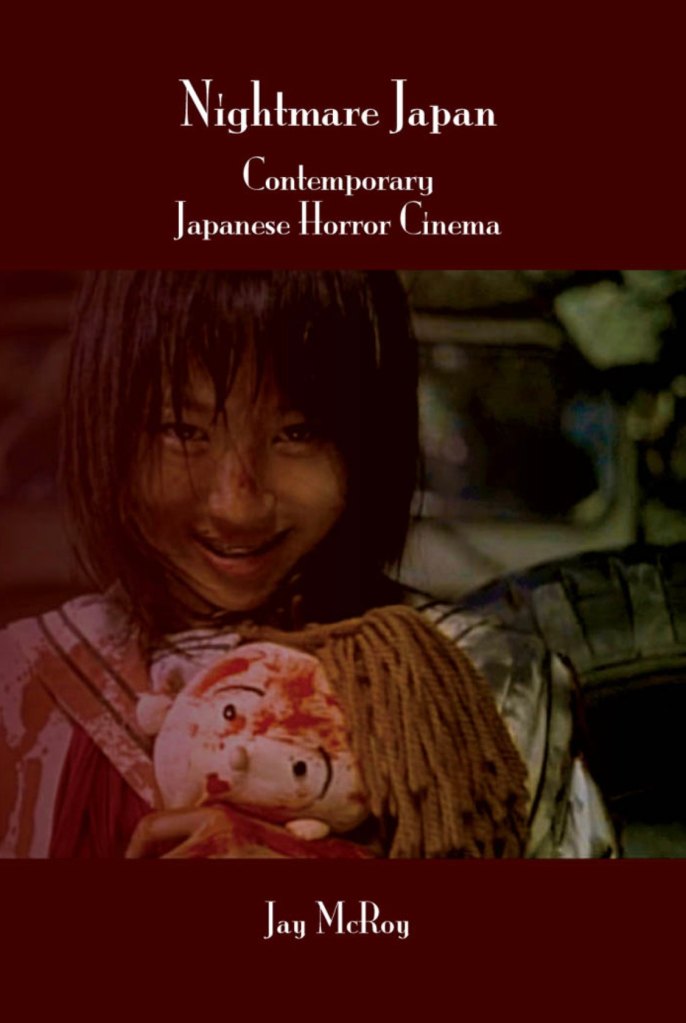

Jay McRoy, Nightmare Japan: Contemporary Japanese Horror Cinema, Brill, 2008. 232 pgs.

Something has been happening with Asian horror, and it took a long time for the intellectual world to try to give it a voice. Since the 1990s, Japanese, Thai, Hong Kong, and Korean horror cinema gradually emerged on the global scene. The novel sensations and aesthetic forms that remain distinct from mainstream Hollywood horror left lasting disquiet in their global circulation. With the unprecedented commercial success of Ringu (1998), the international impact of what is known as “J-horror” redefined both Japanese cinema and horror films. Jay McRoy’s Nightmare Japan is an overdue survey, with abundant historicisation and close reading of an array of unsettling films produced from the 1960s to the early 2000s. Calling for a critical lens with which popular culture can be analysed rigorously and historically, McRoy contends that Japanese horror films are important sites to excavate elusive socio-political sentiments during cultural transformations and crisis.

Rather than reiterating the details of McRoy’s argument, I am most fascinated with the more fundamental question of horror. What is horror? Why is horror cinema grotesque yet appealing? What constitutes the impulse for us to articulate the potential in horror?

The history of “Japanese horror cinema” is an opaque concept. Indeed, as McRoy rightfully notices, graphic images and unsettling stories flourished on the cinema screens in the 1950s and 1960s. Till today, “J-horror” might evoke various associations, from unsettling violence, ghostly spirits, monstrous beings, haunting female corporeality, to apocalyptic settings. However, it is important to note that while McRoy takes “J-horror” as something self-explanatory, it is hardly so. As Alexander Zahlten points out, a film of an old woman turning into a cat and starting to haunt the living might be found under the category of “J-horror” on an online streaming platform today, yet back then, the film was not a “horror film” but a “baneneko film,”a particular genre of films that depict the story of “transforming-into-cats”.

Nonetheless, the missed encounter evinces one thing: the affect of horror is translatable in its impulse. As a scholar of film and media and a regular consumer of horror films, I would contend that the efficacy of horror renders any attempt to distant oneself from the images futile. If horror has an “essence”, it is the unsettlement of any fashionably contemplative distance.

As with many children growing up in Asia, the experience of watching a DVD alone is always associated with a looming worry that Sadako might crawl out from the television box. Japanese horror set a new standard that made many of its consumers immune to the predictable tropes of Hollywood horror. After two decades of watching Ju-on on an old computer in my grandparents’ house, no bloody scenes or murderous dolls can scare me. Certain scenes in The Exorcist certainly evoked a sense of dread during sleepless nights, but it was Ju-on’s collage of unforgettable haunting scenes that happened under the sunrendered daylight as menacing as darkness.

One does not need affect theory to be touched by horror. This is perhaps why McRoy, prompted by the desire to articulate the specificities of Japanese horror, finds it necessary to contextualise it in its historical milieu yet, at the same time, repeatedly returns to “the liminal body”—an elusive conceptualisation that, for McRoy, constitutes the main mechanism of horror. The work begins by asking, if horror has always been associated with uncanny flesh and bones, what is unique about the “Japanese body”? How does Japanese horror, which stands in stark contrast with Hollywood productions, allow us to see bodies in a new light?

Surely, when one intends to locate difference in Japan, one can always find it. The island-nation’s precarious status, its imperialist past and atomic trauma, the U.S occupation, the remilitarisation during the Cold War, bubble economy, radical protests, and so on. Through an analyis of a set of graphic films from the 1980s Guinea Pig series, Sato Hiyasu’s Naked Blood (1996), to the globally renowned Ringu and Dark Water (2002), McRoy highlights how the deformation, defamiliarisation, and contamination of bodies bring forth the force of the grotesque. Treating the liminal bodies as textual metaphors, McRoy claims that this cultural phenomenon refracts the unsettling state of the “national body” that has undergone geopolitical turbulence.

What is fascinating is that, the close reading of the films curiously eludes McRoy’s urge to situate horror. Bodies, made socially and politically, are also the experimental site that rebels against the physical and epistemological limitations that have been imposed upon them. In these films, it is these tensions—between border and transgression, identity and anonymity, “Japan” and the impossible self-identity of the nation, that manifests the crux of horror.

I want to take a different and perhaps unwelcome path to national- and cultural-centred analysis to spend more time pondering this profound phenomenon: over time and across cultures, the horrifying, the eerie, and the uncanny keep manifesting. Different in forms and semiotic functions, the presence of these “negative” beings and affects seems “universal”, whether we like it or not. Even McRoy’s method of reading horror and his attempt to locate heroic resistance in it fall under a classic conception of horror, as the descend of the monstrous has always been associated with a warning.

From Gilgamesh to the Kojiki, from the Bible to Shanhaijing, from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein to Mori Masahiro’s seminal essay “The Uncanny Valley”, the monstrous cries out, alerting the living to the existing undercurrents where future danger seeps in. Philosophical rumination on horror is aligned with such trajectory. Sigmund Freud associates the uncanny with the most intimate experiences that are repressed by social conventions and hence become estranged. Julia Kristeva, through a feminist lens, locates the socially abject—the marginal, the impure, the othered, which have been exorcised from the norms, in the sensation of horror. The vampire is Karl Marx’s favourite metaphor for the capitalist machine, and zombies, as Mark Fisher remarks, embody the symptoms of the industrial wasteland. In this sense, McRoy’s reading of Japanese horror, be it a self-cannibalising doctor or a revenging female ghost, echoes a much longer tradition of unearthing the power of critique in horror, a tradition whose origin is not locatable but is intensely associated with global modernity, rather than “Japanese aesthetics”.

Theorising horror cinema vis-à-vis “nation” is particularly intriguing precisely because of the tension. For, from its inception, cinema is meant to deterritorialise. So is horror. Taking on specific forms and aesthetics, horror comprehends us, in a visceral way. Instead of trying to account how different cultures generate distinct faces and bodies of horror, we might ask, what makes horror continue to enflesh? That is to say, if horror works via reminding us of the “liminal body”, how does it generate bodies anew? Turning away from the discursive and ideological, we might find that the haunting mise-en-scène of Japanese horror lies precisely in its own constant displacement.

Dis-placing horror. The horror of displacement. The Guinea Pig series makes the two-way tunnel clear. The controversial series, presenting extreme graphic exploitation of human bodies, became a widely known urban legend for it “inspired” a real crime. Reality pursues the image, as the image itself inheres a structure of simulation. McRoy points out, at the beginning of the first film in the series, Devil’s Experiment, the director declares that the film which the audience is about to see was “found footage”. The pseudo-documentary form, according to McRoy, is for “heightening the visceral impact generated by the ‘experiment’s’ verisimilitude”. The simulation of murder goes on to have its own life, crossing the body of the image and the social reality. When the efficacy of the simulacra becomes uncontainable and started to set “real horror” into motion, this efficacy itself—its unnameable substance and potency—redefines horror as something that is self-replicating, contagious, viral… Isn’t it familiar?

In Ringu, the curse takes no other form than that of copying and dissemination. The tragedy of Sadako originates from the culpable oppressive social norm, but the deadly haunting is something else. The curse materialises as digital contamination. A video tape whose origin is unknown but easy to copy and a phone call that reaches you via an unseen network conditioned by the new technology of digital spread spectrum, the ghost appears to kill in an era that witnesses the evermore secure yet abstracted and rapid telecommunication. Horror is responding to its own medium of dissemination wrought by a changing media milieu, citing its potency and limits. Sadako is haunting spirit as well as a malleable body that is constant reinvented by the increasing digitalised world and its new potency of erasing the concrete.

Although McRoy focuses on the textual realm, the media ecology underlying the global dissemination of Japanese horror remains almost untouched. If Ringu demonstrates the changing site of haunting, the production history of the Guinea Pig series showcases how the video cinema industry is gaining attention. The viewing of these low-cost films that are made to be released on VHS or video format, is nothing similar to the conventional cinematic experience. This partly explains the vibrant, sometimes messy dissemination of these video films. For children growing up in the early 2000s in China, consuming J-Horror usually indicates a chain of random encounters suturing various sites, images, and sounds together, from the local DVD stores stuffed with various pirated videos, small rental houses sometimes equipped with private screening rooms, to the old-fashioned disc players wired to the back of television boxes or computers that still had those clumsy system units.

The disturbing sceneries of Ju-on are seamlessly superimposed onto my memory of my grandparents’ old house lit by pale chilly daylight. When I thought about Ju-on, the horrifying moaning of Kayako always emerges and is fused with a humming noise generated by the dated computer that tried to “read” the disc. Horror transcends and transgresses. The house that harboured so much joy, also the house where I encountered my first and lasting nightmare was sold three years after my grandfather’s death. Thinking back, the uncanny images and my intimate experience of it also have a face of warning, of the foreboding death and separation. The ghostly nightmare that unsettles many demands a voice, an intelligence that speaks for unnameable sensations that arise from the back of the neck. At this instance, it speaks not only dread, but longing and loss sealed within a space that is soon to disappear.

This might be why, in horror films, it is always those domestic spaces that provide the central stage. But it was Japanese horror, which one does not usually encounter on a big screen and whose circulation is viral yet marginal, renders the nightmare a continued presence. Without the dispositif of theatrical distribution, horror begins and continues in familiar places, haunting one generation after another with a sense of banality. When horror is devoid of spectacular bodies enlarged on the big screen, the duration of it stretches longer. It makes bodies anew, moves, affects, and enfleshes, just like the daily rhythm and its looming discordance.

How to cite: Chen, Junnan. “Enfleshing Horror: Jay McRoy’s Nightmare Japan.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 18 Jul. 2023, chajournal.blog/2023/07/18/nightmare-japan.

Born and raised in Shanghai, Junnan Chen is a PhD candidate at Princeton University, pursuing a joint degree in East Asian Studies and Interdisciplinary Humanities Studies. Before Princeton, she gained her BFA degree from New York University Tisch School of the Arts, focusing on filmmaking and creative writing. She is a thinker and practitioner of both analogue and digital image-making. Her writing and film work explore the themes of time, gender, and visual technology. [All contributions by Junnan Chen.]