{Return to Cha Review of Books and Films.}

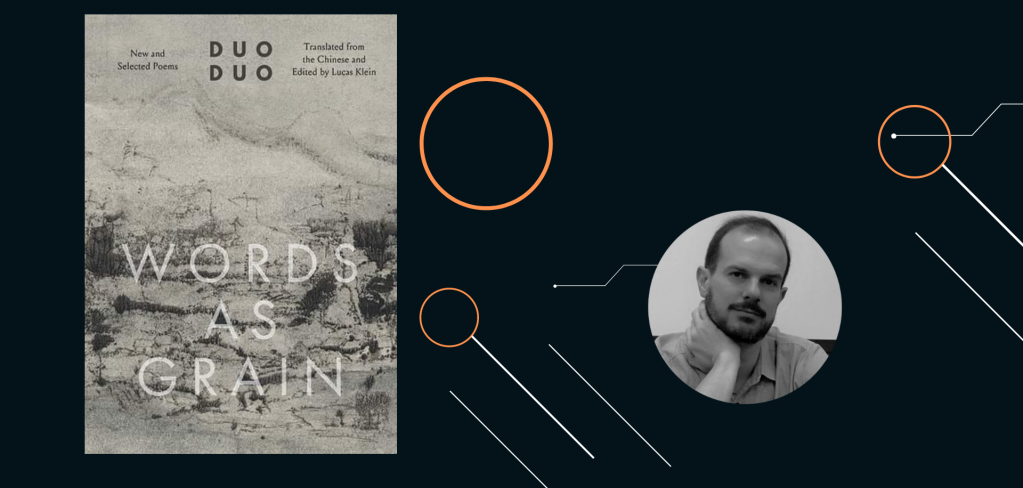

Duo Duo (author), Lucas Klein (translator), Words as Grain: New and Selected Poems. Yale University Press, 2021. 246 pgs.

What follows can only be read as an impressionistic fleeting encounter between a reader and the poems in this collection at a particular moment in time and space: not a particularly fortunate moment, but one emotionally charged and psychologically reverberating, cathartic and healing.

Written by one of the most celebrated contemporary Chinese poets Duo Duo 多多 (1951- ) and translated and edited by the award-winning translator Lucas Klein, Words as Grain 词如谷粒 moves from Duo Duo’s most recent poems back to his earliest ones, with four sections, each forming a period of his life’s journeys and taking its title from one of his poems of that period. “The Force of Forging Words (2004-2018)” collects every single poem written upon Duo Duo’s return to China from 15 years of exile abroad. “Amsterdam’s River (1989-2004)” includes selected poems written during the period of his exile, mainly in the Netherlands. “Delusion is the Master of Reality (1982-1988)” highlights selected poems written during China’s “reform and opening up” period of the 1980s. “Instruction (1972-1976),” the last of the four sections, features some of Duo Duo’s earliest collected poems written in his twenties during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

Duo Duo’s 2004 poem “In Class”, which is about how words may be forged, remade, and granting words agency and centre-stage in his poetry, asks the reader to “let the words have Sundays of their own” (8), while his 2005 poem “Between Two Chestnut Forests Is a Plot of Arable Land” laments that “my parents are now two rows of trees with no complaints” (12). Words, in these instances, are evasive, they may want to take days off, may not be able to escape death, but may also be left behind and have a life of their own. As the final line of the 2010 poem “Drinking Blood in the Wordless Zone” states, “words being what’s said, words’ / remnants, saying everything” (40).

With words at the centre of Duo Duo’s poetry, they take on multiple facets of interesting personas. Words can be incomprehensible, as in the 1986 poem simply titled “Words” 字 (here the English translation did not distinguish between characters 字and words/phrases 词), “they are autonomous / clambering together / to resist their own meanings” (214). The poet finds “no home in words” in a 2012 poem, and the impenetrability of words continues in a 2013 poem “Speechless Between Partners”: “words, in a place far away / are equivalent, but do not meet / the attainment of meaning makes them transform” (77), quite a fitting, meta-portrayal of the difficulties and rewards in any processes of interpretation and translation.

When words fail, image endures, though such dilemmas are again resolutely expressed and confronted in words. Duo Duo continues to highlight psychological and physical constraints in his texts, a sentiment we could all personally identify with, especially in our current state of physical immobility and psychological exhaustion. But Duo Duo also leaves ample room for visual imagination, such as in “In the Room” (2006), “you cannot walk out of this empty room/but see the mountain as a drifting cloud” (16), and in “The Sunlight in the Art Studio” from the same year: “there is still tragedy / but then there is still the landscape” (17). In “Cupping Moonlight Through a Crack in the Door”从门缝掬接月光 (“cupping” is quite a vivid translation for 掬接), also written in 2006, Duo Duo again highlights the unfathomability of texts, “held in these hands / the palms are written over with words unknown”, as well as the physicality and sensuality of images, with a close-up on the threads of lights (19). Such a difficulty and even inability to articulate psychological and mental sufferings in words persists in “Another Phase in Age” (2007): “in the collected works of pain / you are collected, we are harvested/you are separated anew, we are quarantined/the bulk future / runs again toward illiterate fear—” (22).

In addition to probing the dynamics of words and images, Duo Duo is sensitive to multiple sensory stimulations and multidirectional interactions among sounds, images and words. In “Grass—Headwaters” (2007) he can “hear the copper pain in our voices / leave behind the shape of a valley” (23); in “The Statue of the Reading Girl” (2008) he can see “lilac blinked an eye / your feet were sticking out of stone, silently / just then I heard music/ten toes digging into sand/fell and rose like piano keys” (27). The dynamic interactions between voices and silence, and thought and silence become a central theme in Duo Duo’s poetry, and he is determined to “let the dialogue between thought and silence continue” (“Reading Great Poems”, 2011, 49), resulting in words “burst[ing] through the forehead” (“Greeting the Words That Burst Through the Forehead”, 2011, 55).

Such sensory stimulations open up words and poetry to other arts for Duo Duo: “calligraphy is a matter of mind / the way a word is the memory of line / a painting is silent, hiding inside its substance / from pain, that shaped spirit / the severed nerve is made to move” (“The Shang Yang Exhibit”, 2012, 57). Such a sensation intimately echoes what was recorded in the “Great Preface” of Shijing 诗大序, where words and speeches, and singing and dancing, are woven together into an integral network of expressive, intermedial performance. Duo Duo continues to explore such a performative intermediality in his poetry, as in “Just a Few Books” (2014): “we didn’t understand / what music was / through the odd noises of word groupings / a few books rise / in the convection of the word’s linked prayers/let be become be” (89); or in “No Stars in the Sky, No Lights on the Bridge” (2015): “a landscape painting walks to its own margins/shadows like smoke or spirits, still moving” (104).

Such sensory mediations also lead to philosophical musings, as in “Come from Two Prisons” (2007): “distance is only the outcome of measurement” (24), and “Toward the Borges Bookshop” (2008): “myth never regenerates / time overflows from a bowl it seems to have met / before, teaching passersby/not to look at dirty water, but to notice tragedy:/every going in is a going astray / and other than going astray, there will be no going in” (26). In addition to Western influences, such musings also remind readers of many recurring threads in the Chinese philosophical traditions, in particular Daoism, as in “No Dialogue Before Writing” (2013): “the more speech, the less drama / … / all surplus originates in lack / in human nature, there is no mileage / in health, no life / endlessness is not enough illusion/taking shape only when you’re absent” (76), where one cannot help being reminded of Zhuangzi.

One recurring theme in such philosophical musings is a return to the myriad powers of words, as a means to record, rewrite, remember, return, recognise, redress, and restart: “time is not here, but amid permission/waiting for these words to be dug up/to be preserved, above all to be begun” (“No Answer from the Depths”, 2010, 42). In the title poem for the first section of Words as Grain, “The Force of Forging Words” 铸词之力 (2014), the transgressive energy of words is highlighted in the last line, “if words can spill beyond their own bounds/only there, to test the hearing of the end” (93). Such an energy can also be prophetic, as in “From an Unfamiliar Forest” from the same year, “these trees will sway in words / speaking with what’s yet to arrive” (85).

These philosophical musings lead to deeper meta-reflections on the evolving figure of the poet and the act of translation, as in “Poet” (1973): “draped in moonlight, I am upheld as a frail king/letting sentences like a swarm of bees rush in” (239), and “Walking Toward Winter” (1989): “followers in a funeral procession waver east and west / so far away, translation’s sounds in May’s grain waves” (126). At the same time, the impotence of words again surfaces in these self-introspections, as in “Writing That Can’t Let Go of Its Grief Examines the Cotton Field” (2000): “bronze has exiled the witness’s tongue / grass relates the incompetence of words” (170), in “No Mourning Language / The Report of a Canon Is the Start of Comprehension” (2003): “let history lie, let the deaf monopolize listening / words load nothing” (182), and in “In a Few Modified Sea-Jumping Sounds” from the same year, “pain has more clarity than language/the sound of farewell travels farther than that of goodbye” (184).

In this context, “words as grain” emerges in vivid configurations and comes alive as a central metaphor for the forging and remaking of poetry and life, which involves planting seeds, picking weeds, and harvesting grain in the fields, among many more layers of a complex web of meanings. In his poetry over four decades, Duo Duo connects grain, weeds, and fields in his musings on life and death, lonesomeness and expression, speeches and silence, and emptiness and harvest. “The Landscape of Terms Is Not for Viewing” 词语风景, 不为观看 , from 2012 (translating词语 as “terms” here may not be as clear as “words” or “phrases” in the context of this book) is particularly intriguing in this context. It stipulates, “lonesomeness is grain, you cannot not be there/when expensive paper leaves no trace/no words on it, no you / only what cannot be erased can be new/only what’s most real is worth burying” (59). Another fascinating poem, “Talking the Whole Way” from the same year, further grants words agency and connects words and grain: “behind you, words knot their own chain/may emptiness harvest good wheat/there’s a limit to water, but not to fluidity” (60). Such a connection is not something new for Duo Duo. One can trace his connecting words and grain in “News of Liberation’s Exile by Spring” (1982), where he articulates his writing and its crystallsation in the style of planting seeds, picking weeds, and harvesting grain, with a heavy dose of contemplative self-analysis, “in the deeper deeper trust in story/we plant every day, pick every day/having used the fields and taken their secrets/their used lust/was the grain we saved each day” (191).

Lucas Klein, in his translator’s introduction, asks to what degree contextualisation is useful in reading Duo Duo’s poetry (or any poetry), and arranges his selections and translations to move from present into the past, as he considers the recent poems less culturally situated, hence more accessible, than older poems for the non-Chinese reader. Klein continues to emphasise the tension between reading Duo Duo’s poetry “for the argument they make about eternal concepts” or “looking for the contexts…and seeing how the contexts might ground what the poems say” (xvi) and finds in Duo Duo’s poetry a preference for the former.

Klein finds the questions—whether the poems are best read as tied to their contexts or as independent works of the imagination—are the same ones we must ask of translations: whether they are best approached as if tethered to the texts they are representing, or can they take on lives of their own in a new language? He hopes to answer yes to both questions in both cases (xxiii). On the one hand, Klein believes in the potential of poems in translation to take on lives of their own, on the other hand, he also demands accuracy. His goal as both translator and compiler of the poems included in this collection, according to the translator’s introduction, “is to let Duo Duo’s style come through” (xxiv).

As readers, we are fortunate to have Klein’s meticulous work and expert guidance in translating and compiling this excellent volume of Duo Duo’s poems, in close dialogue with and filling important gaps in previous translations and scholarly studies. As a “new” anthology, Words as Grain collects every poem Duo Duo has published since his last collection in English translation from 2002, which includes the full section of “The Force of Forging Words” (2004-2018), accounting for roughly half of the poems translated in this volume. Klein’s powerful translation of these newest poems itself is a major contribution to teaching and researching contemporary Chinese poetry in the English-speaking world. As a “selected” anthology, Words as Grain also includes a selection of Duo Duo’s poetry of the previous three decades, which contains both newly translated poems and poems retranslated by Klein for this volume, another major contribution to the field, as these selections not only carefully contextualise the most recent poems, but also demonstrate Klein’s sensitive approach to the two interpretative possibilities of Duo Duo’s poetry and its English translation, unleashing the transgressive power of imagination in both poetry and translation while respecting their subtle linguistic exchanges and cultural contexts.

Anyone interested in contemporary anglophone poetry and contemporary Chinese culture will benefit from keeping this book by their side, as it is beautifully selected, translated, and produced. At a time when physical travel is severely restricted for many, Words as Grain, with its portable size, can serve as food for thought for our spiritual roaming, both at home and in the classroom, both virtually and in-person.

How to cite: Luo, Liang. “Myriad Powers of Words: Duo Duo’s Words as Grain.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 16 Sept. 2021, chajournal.blog/2021/09/16/review-duo-duo/.

Liang Luo is an associate professor of Chinese studies at the University of Kentucky. She is the author of The Avant-Garde and the Popular in Modern China (Michigan, 2014) and The Global White Snake (Michigan, 2021). She is working on a new book and documentary project, Profound Propaganda: The International Avant-Garde and Modern China.

Pingback: Liang Luo on Duo Duo’s Words as Grain | Notes on the Mosquito