📁 RETURN TO FIRST IMPRESSIONS

📁 RETURN TO CHA REVIEW OF BOOKS AND FILMS

Read “Reading Jin Yong in Translation, Part II” HERE.

Jin Yong, aka Louis Cha Leung-yung (1924–2018). Picture via.

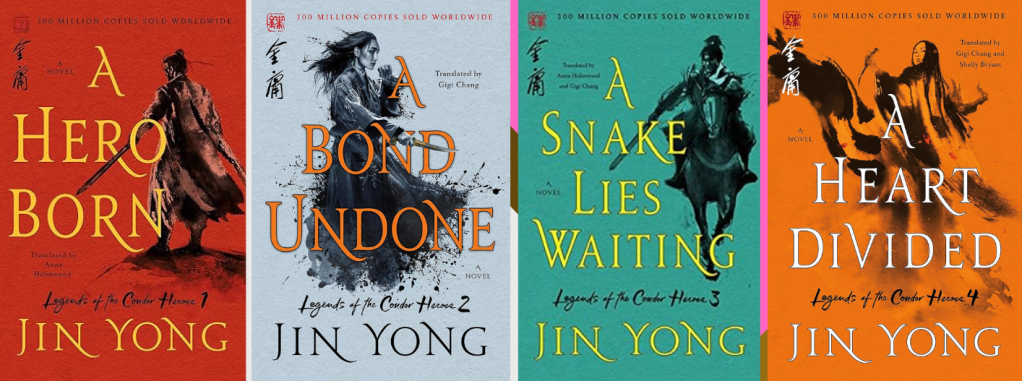

▚ Jin Yong (author), Shelly Bryant, Gigi Chang, and Anna Holmwood (translators) Legends of the Condor Heroes (1957–1959). In four volumes: A Hero Born; A Bond Undone; A Snake Lies Waiting; A Heart Divided, St. Martin’s Press, 2018–2021. 2,032 pgs.

▚ Ann Huss and Jianmei Liu (editors), The Jin Yong Phenomenon, Cambria Press, 2007 (paperback reissue 2023). 354 pgs.

▚ John Christopher Hamm, Paper Swordsmen: Jin Yong and the Modern Chinese Martial Arts Novel, University of Hawaii Press, 2005. 360 pgs.

After years of reading about Jin Yong, I finally got to read him. The book was A Hero Born, the first novel in his four-volume saga Legends of the Condor Heroes, in the new English translation by Shelly Bryant, Gigi Chang, and Anna Holmwood. It took all of thirty-nine pages before I was hooked. This was the decisive passage:

The men in black rushed forward. What they lacked in numbers, they made up for with their superior kung fu.

For years I had been a fan of wuxia movies: the beloved genre devoted to the heroic renegades of a far-off time who roamed the margins of society and settled injustices by virtue of their formidable swordplay and hand-to-hand fighting skills. But in my ignorance, I was unaware that a body of cinema that is by now a part of world culture had a long literary pedigree. It took a score of references—in articles and books about Chinese movies, literature, and history—to give me the first intimation of how much I’d been missing, and to inspire me to learn something about the genre’s most popular author.

That author, as Cha readers probably don’t need to be told, is Jin Yong, aka Louis Cha Leung-yung (1924–2018), the Hong Kong journalist, screenwriter, and publisher who also managed to turn out fourteen large novels and one novella between 1955 and 1972. Most of what I’ve learned about the origins of those novels pleasantly upends what I thought I knew about modern literary production. They initially appeared as daily serials in Hong Kong newspapers—side by side, as John Christopher Hamm writes in his indispensable study, “with reports from refugee camps and accounts of skirmishes across the Taiwan Straits”[1]—before they were published, extensively revised, as triple-decker paperbacks and, later, in an imposing shelf-long Collected Works. By then, Jin Yong had amassed a readership that numbered in the millions, a fan base that would multiply exponentially when the books were adapted, again and again, into movies, TV serials, comics, and video games. It’s hardly hyperbole that a book of critical essays about the author should be titled The Jin Yong Phenomenon.

The Hong Kong imprint of Oxford University Press released a handful of Jin Yong’s novels in English translations around the turn of the millennium—but nearly two decades later, those editions had gone out of print, and fetched exorbitant sums from online used-book dealers. That made it noteworthy when a new translation, of one of his most popular novels, was announced in 2018. First serialised in the Hong Kong Commercial Daily from January 1957 to May 1959, Legends of the Condor Heroes is now available in four fat volumes—A Hero Born; A Bond Undone; A Snake Lies Waiting; A Heart Divided—that run to more than 2,000 pages. For English-language readers to be able to discover, at last, the magnum opus of a storyteller beloved by millions is an event.

A Hero Born opens in the early 13th century. From the north, China is under attack from the Jurchen empire; behind the Jurchens loom the Mongols, led by Genghis Khan. Through a complicated chain of events recounted in the prologue, a young Chinese martial artist, Guo Jing, is being raised by the Mongols and such is his valour, his strength of character, that he becomes a favourite of Genghis Khan himself. None too bright but a fighter of great promise, Guo eventually acquires a love interest, Lotus Huang; spunky, sassy, and a skilled martial artist herself, she is initially more interesting than he is. More importantly for the reader, Guo and Lotus are surrounded by colourful rogues who carry the narrative, in particular the “Seven Freaks of the South”, a band of roving martial artists who adopt Guo and school him in various kinds of hand-to-hand combat. All of these characters in turn are subservient to the “Five Greats”, the most formidable practitioners in the wulin (the community of martial artists), who effectively divide China among themselves.

Various McGuffins keep the ensemble in constant motion, across thousands of miles and hundreds of pages. Guo is initially driven by the need to find out who killed his father; later, a sense of righteous patriotism will motivate him and his allies to protect the homeland from both foreign threats and homegrown oppressors. Several of their foes, meanwhile, are pursuing a legendary manual of martial arts lore that will purportedly make its owner invincible. Both the US and UK publishers of these translations lean hard on comparisons to J.R.R. Tolkien, but for me all the breathless escapades, the constant hurrying to and fro (usually on horseback), evoked memories of Alexandre Dumas and his musketeers.

If you’re going to respond to Jin Yong at all, you should have a taste for exchanges like this one, between two adversaries about to square off:

“You will take my Python whip sitting?”

“You will die tonight, witch!” Qiu Chuji snarled. “Or are we here merely to exchange pleasantries?”

—A Snake Lies Waiting (286)

The theatrical dialogue is a clue that, at least in the early going, Jin Yong’s characterisation can be fairly rudimentary. The heroes are valiant and the bad guys are treacherous. Many supporting players are given one or two idiosyncrasies that recur repeatedly over all four volumes, but they tend to be most memorable for their particular fighting style. There are two gratifying exceptions. The first is Zhou Botong, the “Hoary Urchin”, an ageing irreverent Taoist imp whose life lessons for young Guo are distilled into one line: “Kung fu is a store of infinite fun.” The other is one of Jin Yong’s female villains, the fearsome “Iron Corpse” Cyclone Mei—terrifying on her first appearance (she can pierce her opponents’ skulls with a single strike of the hand), she later acquires a tortuous backstory that imbues her character with a gravitas—a multidimensionality—that wouldn’t disgrace a more self-consciously literary novel.

Cyclone Mei is introduced in an epic set piece that takes place about a third of the way through A Hero Born: a midnight confrontation, at the top of a mountain, set against thunder and lightning, in which the Seven Freaks of the South contend with her and Copper Corpse, her equally sinister partner in life and combat. As many Western fans of wuxia movies probably have, I first approached Jin Yong’s novels with one question primarily in mind: How are the fight scenes? The confrontation with Iron Corpse and Copper Corpse allayed any concerns I might have had about the books not being the equal of their cinematic counterparts. For page after page, as the Seven Freaks pivot and weave around their enemies, hard pressed to defend against the duo’s fearsome “Nine Yin Skeleton Claw” kung fu, the reader revels in a sense of transparency, as though there were no distance between the book in hand and the action unfolding in the mind’s eye. (The casualties sustained on both sides of the fray, meanwhile, are a sobering lesson in how Jin Yong’s roughhousing has mortal consequences.)

The battle between the Freaks and the pair of Corpses begins with the arresting image of a shadow, seen from a distance, flitting across a moonlit plain: one of the earliest instances of Jin Yong’s ability to create widescreen panoramas for the printed page. Legends of the Condor Heroes abounds in such cinematic moments, and it’s only when you pause to remember you’re reading a novel from the 1950s that you realise it would be years before technical advances—in editing, in wire work and other special effects—would allow the movies to match some of his most vivid imagery. Consider this freeze-frame from A Snake Lies Waiting:

Wanyan Honglie watched the men fight, leap, and dodge. One leaped up, another crouched down, until suddenly they were both stiff, like corpses. Not even their hands trembled. It was as if they had stopped breathing. A strange sight indeed. (186)

Or a moment from A Heart Divided, so concise I have to remind myself I didn’t see it on a big screen:

A shadowy blur was speeding toward them, gliding over each gap on the bridge as if its body were immaterial. The improvement in her kung fu was frightening to behold. (122)

It’s worth remembering that these effects are being recreated from another language. Writing about Lee Child’s Jack Reacher novels a few years ago in Bookforum, Michael Robbins identified “utilitarian” prose as integral to the success of Child’s action sequences: “Words impart information. Sentences tell you what is happening…. This happened, so that happened, he would have done this, but he did that, and he did it like this. Nothing fancy.”[2] A similar no-fuss style accounts for the lucidity of Jin Yong’s fight scenes, which Shelly Bryant, Gigi Chang, and Anna Holmwood handle admirably, but the cultural context must have made special demands on them as well. Note the precision and variety of the action verbs in this passage from A Snake Lies Waiting, rendered by Holmwood and Chang:

Dog-beating Kung Fu utilized eight types of attack: Trip, Hack, Coil, Jab, Flick, Draw, Block, and Spin. As the duel continued, Lotus settled into a series of coil moves, curling the cane around the staff like a vine winding its way up a tree. The tree trunk could grow tall or wide, but it could never untangle itself from the vine’s grip. (389)

There may be no more literal illustration of Eliot Weinberger’s dictum that “translation is movement”. Passages like this are the translators’ equivalent of the “lightness kung fu” that Guo’s mentors are constantly trying to inculcate in him—a level of mastery that, among other feats, enables its practitioners to walk on air.[3]

Not everyone shares in the general adoration of Jin Yong and wuxia. One famous example will stand for many.

In The Drunkard, a seminal 1962 novel by the Hong Kong writer Liu Yichang, the title character is a morose alcoholic litterateur, a would-be avant-gardist, for whom wuxia serials are the lowest form of literary hackwork, barely a step above pornography. “Stuff about chopping people’s heads off from a thousand miles away is the only thing that makes money,” he laments early on, in a vein that continues for nearly three hundred pages. An editor’s endnote to the English translation of The Drunkard published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong Press in 2020 perpetuates the condescension with a reference to “the essential silliness” of the wuxia genre.

To which a Jin Yong fan might reply, in the words of the English novelist Anthony Burgess: “It is unwise to disparage the well-made popular.”[4]

Besides: Jin Yong is a poet. The poetry isn’t in his unadorned prose (see “utilitarian”, above) but in a particular area of metaphor that is presumably unique to the martial arts genre. These are the names he gives to the variety of moves developed and refined within the various schools of kung fu his characters belong to—a seemingly bottomless catalogue of punches, kicks, dodges, and feints that each has its own suggestive title.

They begin in a more straightforward vein, with a descriptive function that speaks for itself: Bronze Hammer Fist, Wayfaring Fist, Iron Broom Kick. But soon even these more basic names begin to evince a dizzying variety. Dragon-Subduing Palm already sounds impressive enough, but when you subsequently learn that the repertoire also includes a Heartbreaker Palm, a Lotus Palm, and a Cascading Peach Blossom Palm, you begin to fathom the level of skill that Jin Yong’s master martial artists have attained. The names can take a homely comic bent—Flip the Dog Belly Up; Snatch from the Mastiff’s Jaw—or they can go in a more mythic direction, as in Hidden Dragon Soars into the Heavens; Magic Dragon Shakes His Scales; Haughty Dragon Repents. A more wide-angle subcategory gives us Jin at his most evocative: Dividing the Clouds and Moon. Thunder Rocks a Hundred Miles. And my own favourite, the stirring Trident Searches the Sea by Night.

Of course, as many wuxia fans know, these names exist in the context of a single overriding metaphor—perhaps the most striking of all. Every one of Jin Yong’s characters, friend and foe alike, is a denizen of the jianghu: a term that translates as “rivers and lakes”, but which demarcates the underworld, or alternative society, with its own elaborate codes, rituals, and hierarchies, that the martial artists inhabit. Literary scholar Xiaofei Tian calls the jianghu a “special expanse”, “a fantastic spatial and temporal structure” locatable not only in “wild, fanciful landscapes” but also in some recess of the human mind; she helps pin down its unique allusiveness when she writes:

Jianghu is the wild “badlands” filled with desperados and outlaws, but as a term indicative of a subjective space as well as a geographic space, it permeates all social classes from bottom to top, from beggars to court officials or rich businessmen.[5]

The beauty of these metaphors—the jianghu as well as the names of all the martial arts moves—comes, in part, from the vivid mental pictures they give us. (And how fortunate for English-language readers that jianghu retains its picturesque qualities in translation.) But the poetry also derives from an intimation of a remarkably comprehensive way of looking at, and being in, the world: an almost total system in which everything represents another thing, and in which two men fighting in a bamboo grove can be made to seem the embodiment of cosmic forces. It’s a tradition that goes back at least as far as the eighth century, to a poem by Du Fu in which a woman performing a sword dance sets heaven and earth to swaying through the power and grace of her undulations:

[She] soared upward like a host of gods circling with dragon teams.

She came like a peal of thunder withdrawing its rumbling rage,

then stopped like clear rays fixed on the river and sea.[6]

To anyone new to Jin Yong’s fiction, it might seem a little extravagant to draw a link between one of his blockbusters and the heights of Tang Dynasty verse. But the fact is that Jin Yong himself unmistakably claims such a lineage. The novels are studded with allusions to classical Chinese culture: not only history and literature but also Buddhist sutras and other foundational texts like the I Ching and the Tao Te Ching, the cumulative effect of which is to make the books, as Marcel Theroux has written, “a wonderful initiation into a lifelong enthusiasm for China, its history and civilisation, its vast and chronically misunderstood presence in the world”.[7] (All four volumes of Legends of the Condor Heroes include helpful appendices that elucidate Jin Yong’s web of references, but it’s a shame that the editorial apparatus overlooks something as basic as a map of 13th-century China, which would have been a better use of space than a set of anodyne pen-and-ink illustrations that don’t really add anything to these editions.)

The Buddhist and Taoist touchstones are crucial because they alert us to how Jin Yong’s fiction means to convey an ethical and philosophical system underlying all the beatdowns, just as the best wuxia films do. For Western readers who may still be understandably fixated on Bruce Lee, the point is worth making that in the imaginative world of the wuxia, kung fu isn’t strictly about fighting skills: It can apply equally to any practice that requires concentration and training. One of the most piquant episodes in Legends of the Condor Heroes is the showdown in Book Three between two of the Five Greats: After a good deal of preliminary gamesmanship, the two martial arts masters face off in a duel—on zither and flute. Surreptitiously listening in, Guo Jing realises, “It’s a contest of internal kung fu,” which he intuits because his own pursuit of internal or neigong kung fu, a mental awakening that corresponds to the bodily discipline, is an important thread in Jin Yong’s overall weave. An early flash of insight comes during Guo’s study of meditation with a Taoist master:

He had never, in all his years in the wulin, seen anything like this Orchid Touch kung fu, a technique that emphasised speed, accuracy, surprise and clarity. It was this last aspect, clarity, which really distinguished the accomplished practitioner, as it principally required a stillness of the heart, graceful movement born of an unhurried mind. (A Hero Born, 354)

Gradually, we realise that Guo’s path to martial arts mastery is part of his larger spiritual development, and that the novel he stars in is a Bildungsroman that just happens to be full of punches and kicks. The graceful way in which Jin Yong situates his hero within this wider framework is part of what makes Legends of the Condor Heroes something more than a breathless adventure story, and helps to account for its enduring hold on generations of readers.

For months, these books held me rapt, on buses, subways, and trains. Happily, Legends of the Condor Heroes concludes, in the best storytelling tradition, with the tease that has beckoned audiences since time immemorial: To Be Continued. The saga will resume, we’re told, in The Return of the Condor Heroes—which in fact is only the first of Jin Yong’s two four-part sequels to the original work, making for a grand total of twelve volumes altogether. Three cycles, twelve volumes, thousands of pages: a store of infinite fun.

NOTES

[1] John Christopher Hamm, Paper Swordsmen: Jin Yong and the Modern Chinese Martial Arts Novel (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2005), 29.

[2] Michael Robbins, “A Rumble Offering”, review of The Sentinel: A Jack Reacher Novel by Lee Child and Andrew Child, Bookforum, December/January/February 2021, https://www.bookforum.com/print/2704/jack-reacher-s-good-fights-24265.

[3] In the case of Jin Yong, routine quibbles about a translator’s choices can quickly tip into the closely held prerogatives of a passionate and vociferous fan base. Jo-Ann Chiu at Ricepaper and the website Wuxia Wanderings are two helpful points of entry into these debates.

[4] Anthony Burgess, 99 Novels: The Best in English Since 1939 (London: Allison & Busby Limited, 1984), 74.

[5] Xiaofei Tian, “The Ship in the Bottle”, in The Jin Yong Phenomenon (Youngstown, NY: Cambria Press, 2007, reissued 2023), 220.

[6] Stephen Owen, Ding Xiang Warner, and Paul W. Kroll, “On Seeing a Student of Mistress Gongsun Dance the ‘Sword Dance’”, translated by Stephen Owen, The Poetry of Du Fu, Vol. 5 (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton, 2016), 335, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501501890.

[7] Marcel Theroux, “A Hero Born by Jin Yong review—the gripping world of kung fu chivalry”, Guardian (UK), March 16, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/mar/16/hero-born-kung-fu-chivalry-wuxia-jin-yong-legends-condor-heroes-translation.

How to cite: Tompkins, Jeff. “Kung Fu Is a Store of Infinite Fun: Reading Jin Yong in Translation, Part I.” Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, 29 Feb. 2024, chajournal.blog/2024/02/29/jin-yong-i.

Jeff Tompkins is a writer and zine artist in New York City. His articles and reviews have appeared in The Brooklyn Rail and Words Without Borders, among other outlets. [All contributions by Jeff Tompkins.]